Usha Vance Is Reading The Iliad, a Poem About Male Rage. Its Famous Translator Sees Irony.

“JD Vance’s wife is reading a more than 800-page book about men fighting to control women’s bodies, waging war, and ‘refusing to accept a loss.’”

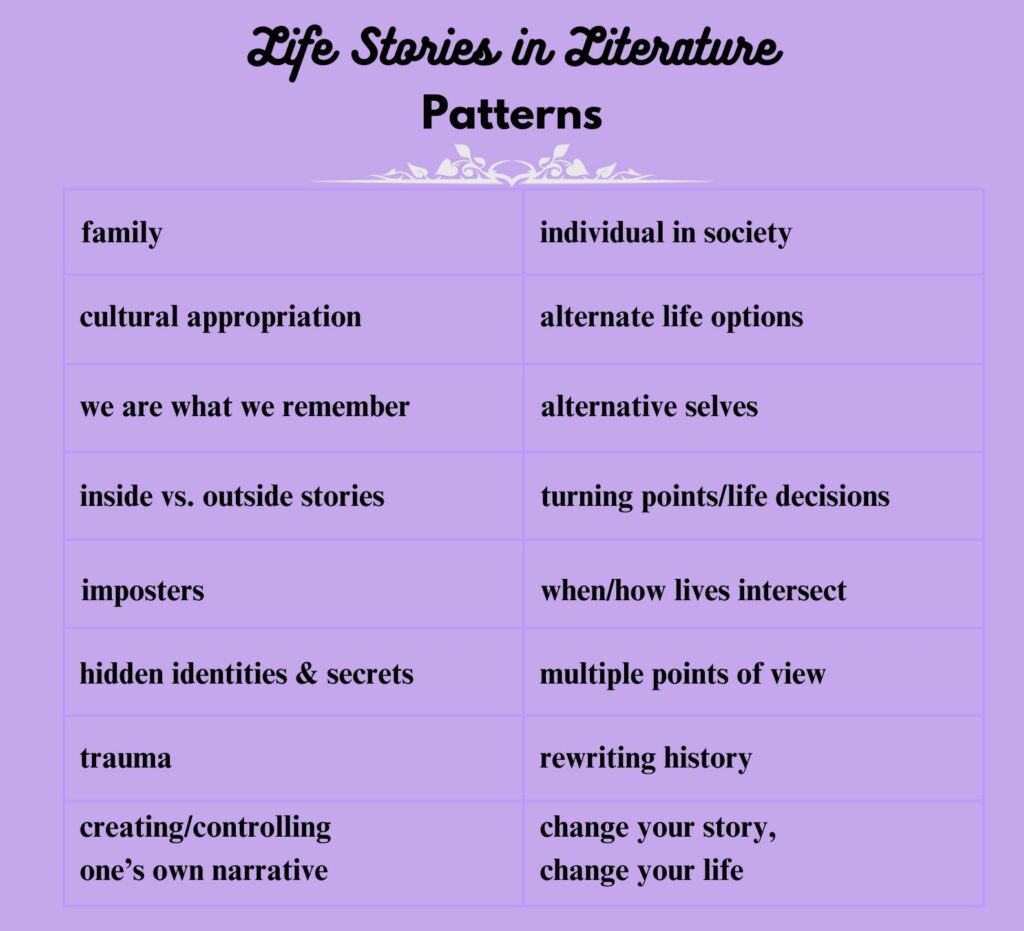

This article ticks off so many Life Stories in Literature patterns: rewriting history, giving voice to previously marginalized people, searching for one’s identity, seeing through another person’s eyes, understanding the relationship between literature and culture.

Most informative is the discussion with Emily Wilson, the translator of the Iliad that Usha Vance was seen carrying.

Writers & Gamers Reading List

I don’t play video games and had never thought about the similarities between novels and game narratives until I read Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin. Here, the American Writers Museum, located in Chicago, Illinois, describes its latest exhibit: “Our current special exhibit, Level Up: Writers & Gamers, explores how Americans use tabletop role-playing games and video games to define and respond to our culture.” The reading list includes books “about or influenced by gaming.” Of course Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is on the list.

The Toxic Legacy: Coming-of-Age in Psychological Suspense

Coming of age is a foundational time in identity development. But not everyone grows up in a loving, supportive family environment. Novelist M.M. DeLuca describes novels that tell their stories:

in the genre of psychological suspense, this emotionally-charged journey becomes as treacherous as navigating a minefield. And, rather than celebrating the power of familial bonds, the genre offers an unflinching reflection of the darker undercurrents of family dynamics, laying bare the emotional manipulation and abuse that can linger within seemingly ordinary households. Writers of psychological suspense go beyond the closed doors and into the shadows to reveal the chilling details of homes that have become battlegrounds where power dynamics are warped, morality blurs and survival is all that counts.

As this millennium began, books reflected tragedies and anxieties

“Both nonfiction and fiction were colored by 9/11 and the other tumultuous events of the 2000s.”

This piece is from a series of articles in The Washington Post celebrating this year’s 75th anniversary of the National Book Awards. Francine Prose, a finalist for the National Book Award in 2000 for her novel Blue Angel, discusses books of the 2000s and their relationships to the society of their time.

Writing Online Fiction in China

“Many amateur ‘fan fiction’ writers on the Chinese internet use real history as a canvas for time-travel stories that often break the fourth wall.”

In this article for digital knowledge library JSTOR, Livia Gershon writes “Unlike in the US, where (with some exceptions) online fiction stands outside the literary establishment, it’s fairly common for online writing in China to end up published in print or adapted as television dramas, allowing some writers to become multimillionaires.”

8 Books That Will Leave You Questioning if Your Memories Are Real

“We can’t always trust the stories we tell ourselves”

“The more I learn about memory, the less I trust my own,” Lindsay Starck tells us. “The stories we tell ourselves about our past are crafted and filtered, mutable and unreliable.”

The books she lists here deal with the “matter of borders: inside versus outside, truth versus dream, fact versus fiction.”

So You Think You’ve Been Gaslit

“What happens when a niche clinical concept becomes a ubiquitous cultural diagnosis.”

Note that this descriptive slug is a statement, not a question. Leslie Jamison explains at length how gaslighting “has effectively become an umbrella that shelters a wide variety of experiences under the same name.” I was especially intrigued in her discussion of the connections between gaslighting and personal narrative, which comes up a bit more than half-way through the piece.

The Questions We Don’t Ask Our Families but Should

“Many people don’t know very much about their older relatives. But if we don’t ask, we risk never knowing our own history.”

As a professor of anthropology, I have always been fascinated by the stories that families tell, and a few years ago, I started researching the tales that are passed down from generation to generation. Part of my motivation was personal. When my mother died in 2014, I realized how much I didn’t know about her life. I never asked the questions that haunt me now—questions about what interactions she had, what it was like to live in her time in the places she did. I wish I had a fuller sense of her as a person, especially how she was when she was young, with a lust for life.

This article is adapted from The Essential Questions: Interview Your Family to Uncover Stories and Bridge Generations by Elizabeth Keating.

Tolkien’s Middle-Earth wasn’t a place. It was a time in (English) history.

Tim Brinkhof discusses a current interpretation of Tolkien’s masterpiece that “argues that the various regions of Middle-earth visited in The Lord of the Rings were inspired by, and intended to represent, specific moments in English history.”

A college course that’s a history of the future

In a series called “Uncommon Courses,” news site The Conversation discusses what it calls “unconventional approaches to teaching.” Adam Jortner, Goodwin Philpott Eminent Professor of Religion at Auburn University, explains his course called Science Fiction as Intellectual History: “I usually pick three big plot ideas from sci-fi: alien encounters, time travel and superhuman abilities. Then we trace the development of those ideas, primarily through American fiction.”

© 2024 by Mary Daniels Brown

I was very fortunate to learn more of my mother’s early life from her in the last few years of her life.

I had hoped to do the same, Liz. Unfortunately, my mother’s most pronounced symptom of the onset of dementia was aphasia. The last thing she said to me was, “I want to tell you . . .” And that was it. It’s too bad she waited so long to want to tell me something.

I’m very sorry to hear that, Mary.

That’s interesting that the path to publication is so different for Chinese writers than American ones.

I thought the same thing, Joy. Thanks for reading and commenting.