Related Post:

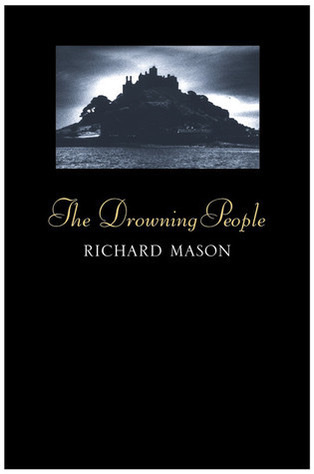

The Drowning People by Richard Mason

- Time Warner, 1999

- Hardcover, 352 pages

- ISBN 0-446-52524-3

Writing the post about how The Drowning People contributed to my development in reading reminded me to put this novel on my list of books to reread this month. I’m glad I reread it. What I initially remembered was how the gothic elements gave the novel an air of timelessness and oppressiveness. What I didn’t remember were the explicit life-story aspects of the narrative.

The story opens with the first-person narrator, James Farrell, telling the reader that he has just killed his wife of 40 years. He then tells us:

If ever I am to put the events of my life in some sort of order I must begin the sifting now; I must try, I know, to understand what I have done; to understand how I, at the age of seventy, have come to kill my wife and to feel so little remorse over it. (p. 6)

As novelist Olesya Salnikova Gilmore explains, gothic elements underscore “the darkness within”:

Gothic fiction and, more broadly, horror, shows us the darkness within ourselves and our worlds. And since our world today seems very dark indeed, it reflects our deepest, greatest fears, our most insecure vulnerabilities as humans. It horrifies, it entrances, it romances, it invites escape, all in equal measure. Like other genres, gothic fiction doesn’t need to be static. It can change with the times, encompassing our modern realities, sensitivities, and preoccupations.

The novel is set in Great Britain, where Farrell grew up in a solidly middle-class family. His parents understood and accepted their place in society and followed its culturally accepted expectations and beliefs, which they dutifully passed on to their son. But James’s worldview began to expand when he was a student. He met the beautiful look-alike cousins Ella and Sarah Harcourt, with their ancient ancestral home on an island off the coast of Cornwall, and was drawn into their upper-class world of parties, money, and notions of behavior appropriate for their social position, including whom one was expected to marry.

The gothic elements and the life-story aspects of the narrative work together to shape the reader’s reaction as the now-seventy-year-old Farrell unfolds his life story. He describes how his values changed during the pivotal period between adolescence and young adulthood as he moved within his expanded circle of acquaintances.

Several times he describes his actions during that time as a kind of performance, as if he’s a detached spectator watching himself in a movie: “I watch myself saunter over to the bench where she [Ella, with whom he will later fall in love] is sitting” (p. 12). But as the young, detached spectator morphs into the much older man, Farrell comes across as aloof, snobbish, even arrogant, someone who thinks himself superior to the average human:

Had I never considered any system of values beyond that of the drawing room, I would certainly never have killed Sarah. But then Sarah deserved to die; and had I never strayed from the confines of polite morality, from the limits set by sermons preached in school chapels to tweed-suited audiences, I would never have been able to punish her as she deserved. (p. 20)

As his recitation of his life progresses, he continues to attribute his past actions to youthful ignorance: “I had neither wisdom nor experience, you see; I was a child playing an adult’s game” (p. 215).

And here I will leave the rest of James Farrell’s story for you to discover. Richard Mason continues to use life-story psychology to weave a complex plot with rich characters worthy of the gothic setting and atmosphere that illustrates how that historical literary technique can function in a contemporary book. In fact, The Drowning People could serve as the basis for a detailed study in how a novelist can use life-story theory to build a compelling fictional work. But that analysis would be a long, graduate-level essay, not a book review, and would require ditching my no-spoilers approach for this blog.

When I originally read this novel back in 2001, I had not yet studied up on narrative identity theory and was therefore not even beginning to think about how life stories can inform fiction. That’s probably why my memory of the novel focused on the gothic elements of storytelling. But perhaps Mason’s use of life-story psychology stuck in my unconscious and continued working there until I had the rest of the information I needed to recognize the pattern of Life Stories in Literature.

Study Notes

8 Brooding Gothic Mysteries Set on the British Isles

Gothic Fiction with a Twist

Gothic Elements in Shirley Jackson’s “We Have Always Lived in the Castle”

© 2024 by Mary Daniels Brown