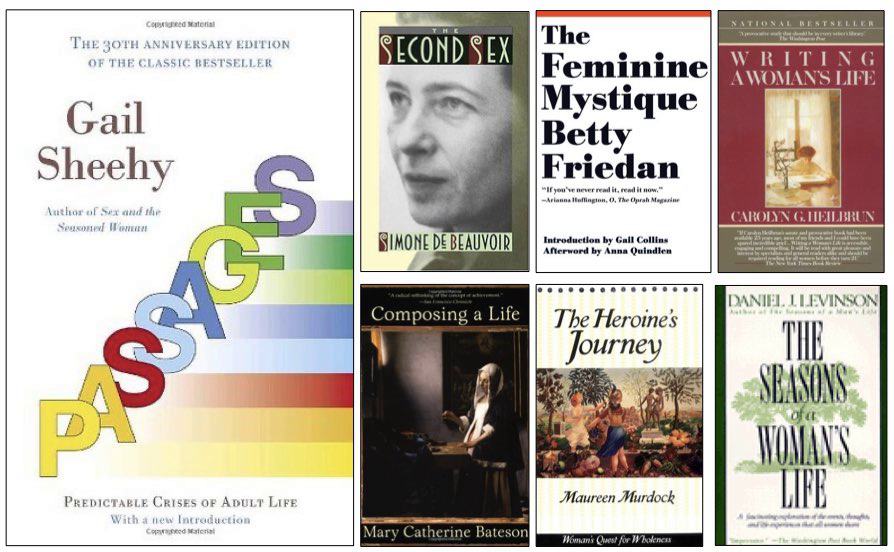

This month’s starting book was a best-selling self-help title in the seventies – Passages by Gail Sheehy, published in 1976.

I read Passages before I started keeping a reading journal, so I can only estimate when I read it. It would have been in the mid 1980s, as my 40th birthday approached. I remember it as a book aimed at women and was therefore surprised by the Goodreads description that indicates the book was written for both men and women.

Perhaps I remember Passages as a book aimed at women because I became interested in women’s memoirs at around the time I read it. In my memory, Sheehy’s book piqued that interest, which continued to grow until 2005. That’s when I decided to go back to school because of a vague but insistent feeling that there were things I still needed to learn. I ended up studying life stories and, after six years, received my doctorate in psychology.

Although I don’t remember anything specific from Passages, I associate it with an abiding interest in life stories, particularly women’s life stories. I wrote my dissertation on the life stories of five early women physicians from the United States. For that project I read several books about women’s lives.

So for this month’s exercise I’m going to share six of those nonfiction books with you in a thematic chain. This approach fits well with the celebration of March as Women’s History Month.

first degree

The Second Sex (1949) by Simone de Beauvoir is a seminal work in the study of women’s lives. She examines the Western notion that man is the default norm against which women are contrasted, thus relegating women to the position of “other.” This otherness, in turn, has lead to inequality between the sexes by codifying women as inferior to men.

second degree

Next is The Feminine Mystique (1963) by Betty Friedan. This ground-breaking work described “the problem that has no name.” Without knowing exactly what to call it, Friedan had discovered that smothered feeling women felt because of unquestioned social beliefs that urged them to be content with home and family, and of institutions of higher learning that minimized their intellectual potential by turning homemaking into a glorified academic discipline.

third degree

In Writing a Woman’s Life (1988), feminist scholar Carolyn G. Heilbrun argues that men have always had narrative structures such as the quest motif and the warrior’s adventure through which to tell their stories, but these narrative models have been denied to women because the behavior they illustrate is unwomanly. It wasn’t until the last third of the 20th century that women recognized the narratives that had been controlling their lives for centuries. Since then, women have been searching for new forms of expression to explain their lives.

fourth degree

Composing a Life (1989) is Mary Catherine Bateson’s “treatise on the improvisational lives of five extraordinary women. Using their personal stories as her framework, Dr. Bateson delves into the creative potential of the complex lives we live today, where ambitions are constantly refocused on new goals and possibilities. With balanced sympathy and a candid approach to what makes these women inspiring, examples of the newly fluid movement of adaptation–their relationships with spouses, children, and friends, their ever-evolving work, and their gender–Bateson shows us that life itself is a creative process” (Goodreads).

Bonus connection: Gail Sheehy earned an M.A. in journalism from Columbia University, where she studied on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship under cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, the mother of Mary Catherine Bateson.

fifth degree

Many of these books discuss the need for women to find narrative forms different from the traditional patterns men have used for centuries to record their life stories. I took a memoir-writing workshop (probably some time around 2000) with Maureen Murdock, author of The Heroine’s Journey (1990), who calls memoir a form of mythology. History is written by the victors, and for centuries those victorious writers have been men. As a result, women’s stories have largely been erased from history. Over the last 50 years of so, memoir has exploded as a means for women to record and discuss the stories of their lives.

sixth degree

Almost 20 years after Yale psychologist Daniel J. Levinson renewed interest in life passages with The Seasons of a Man’s Life, he published The Seasons of a Woman’s Life (1996). Levinson’s books advance the thesis that both men and women continue to grow and change throughout their lives.

Everything I learned about the psychology of life stories—which is a decidedly nonfiction subject—has made me a better reader of fiction because fiction is a creative expression of imagined peoples’ lives. Focusing on Life Stories in Literature helps me understand and appreciate the work of novelists who use their skills to create stories and characters that imaginatively probe the questions of the meanings of human experience.

© 2023 by Mary Daniels Brown

Another feminist chain here… self-helpful too!

Getting older has made me progressively more aware of feminist issues, I must admit. Thanks for reading and commenting, Davida!

Female centered books are a strong theme this month on Six Degrees.

Clever chain!

Have a wonderful March!

Elza Reads

Thanks, Mareli! I enjoyed Elza’s list this month, esp. the first two: Passage to India and The Far Pavilions. And I love the layout of your site and am now going to return to study it further. . .

Some powerful works on here that will find their way to my reading list; the first is the only one that’s currently on the list. Great chain!

Thanks, Mallika!

That’s a really interesting point about memoirs being a form of mythology. That does explain the recent profusion of memoirs. Fascinating chain.

Thanks, Linda!