I take no pleasure in reporting this.

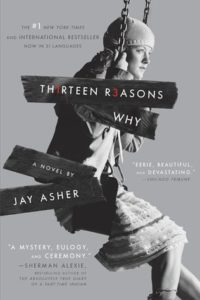

Back in 2017 I read Jay Asher’s book Thirteen Reasons Why in preparation for the Netflix series. I wrote about the mixed messages I found in the book, which disturbed me so much that I refused to watch the Netflix production, in Thoughts on “Thirteen Reasons Why.”

Now The New York Times reports that:

a new study finds that suicide rates spiked in the month after the release of the series among boys aged 10 to 17. That month, April 2017, had the highest overall suicide rate for this age group in the past five years, the study found; the rate subsequently dropped back into line with recent trends, but remained elevated for the year.

In Month After ‘13 Reasons Why’ Debut on Netflix, Study Finds Teen Suicide Grew

Suicide rates for girls aged 10 to 17 — the demographic expected to identify most strongly with the show’s protagonist — did not increase significantly.

The NY Times article contains a link to the study abstract as posted by the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Thirteen Reasons Why is the story of 13 tape recordings left by a young woman who committed suicide after being bullied and shamed at school, which is why the newspaper article identifies girls as “the demographic expected to identify most strongly with the show’s protagonist.”

However, I was most concerned with the way the book presents the effects that the recordings had on the young man who had tried to talk with the girl. My heart sank when I read this in the article abstract: “Contrary to expectations, these associations [of increased monthly suicide rates] were restricted to boys.”

This study reminds us that words have power, whether they appear in print form in books or in dramatic form in television shows or movies.

Update

5/6/2019

I’m now seeing more discussion of the Netflix series Thirteen Reasons Why prompted by the study discussed in The New York Times.

Stephen Marche in The New Yorker article “Netflix and Suicide: The Disturbing Example of ‘Thirteen Reasons Why’” reports that, before Netflix aired the series, many experts warned “that a wide array of studies has linked portrayals of suicide in the media to increases in the suicide rate.” And, Marche continues, “Netflix responded to the controversy surrounding the release of the show with bromides.”

And there’s more:

Our understanding of the interaction between pop culture and real-world consequences is fraught with lazy assumptions and fearmongering, and the best research is never utterly conclusive, but suicide is mostly an exception to this state of confusion. Suicide contagion has been observed for centuries.

And this:

Those who predicted the association between the show’s release and a rise in the suicide rate have met the fate of so much expert opinion in the twenty-first century: their predictions were ignored or cast into doubt by financially interested parties; the research, which came too late to matter, gave evidence that the predictions were true; and there were no consequences.

Constance Grady for Vox approaches the question of how difficult it is to prove whether the TV series is responsible for the death of teenagers:

So when I talked to academics about the study, all of them said that they continue to be wary of shows like 13 Reasons Why — but they also said the study is nowhere near proof that 13 Reasons Why is actually responsible for the death of teenagers. And in part that’s because, regardless of whether such a relationship might exist, it’s nearly impossible to prove.

Grady consulted with other experts and researchers. Her article also includes a list of online resources for learning more about how to help someone you think might be suicidal.

CNN reported on the recent study’s findings here.

Finally, you can read the report released by the National Institute of Mental Health, which funded and conducted the study, here.

© 2019 by Mary Daniels Brown