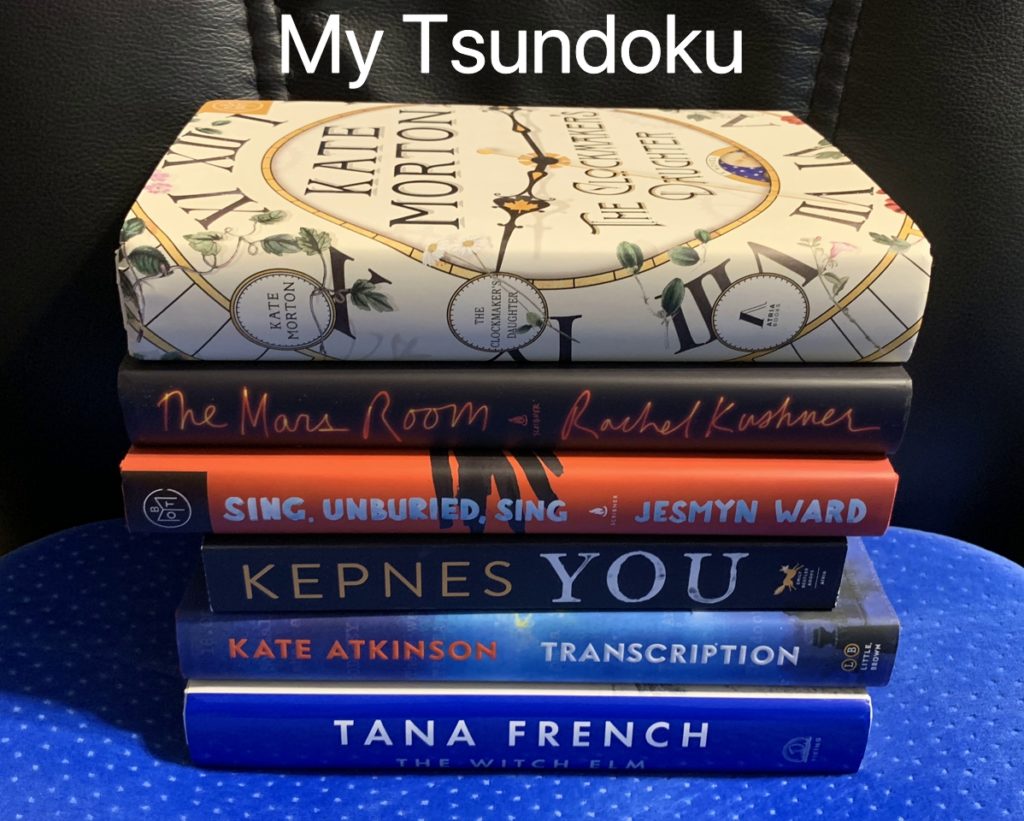

Show Us Your Tsundoku!

Loosely translated as the practice of piling up books you might never read, the Japanese word tsundoku seems to be everywhere right now. In recent months, The New York Times, the BBC, Forbes, and plenty of others have reported on the phenomenon.

Here’s the feature’s subtitle: “We want to see your shameful stacks of unread books.”

Well, I, for one, see absolutely no shame in my collection, seen at the top of this post. I do have to admit, though, that this isn’t my entire collection of not-yet-read books. There’s no way I could fit all of them into one photograph.

How about you? Are you willing to share your tsundoku photos in the comments?

Learning another language should be compulsory in every school

Every time we travel to another country, I’m amazed at how fluent the local people are in languages other than their native language. Many people even speak two or more languages in addition to their language of origin. When I ask them at what age they started learning foreign languages, they often give an age between 8 and 12 years. And the reason they most often give is that they are required to choose another language in school.

We U.S. residents could learn a second language, too, if it were an academic requirement. In this article Daniel Everett, dean of arts and sciences, professor of global studies, and professor of sociology at Bentley University in Massachusetts, explains why he believes:

Now, after spending most of my adult life in higher education, researching languages, cultures and cognition, I have become more convinced than ever that nothing teaches us about the world and how to think more effectively better than learning new languages. That is why I advocate for fluency in foreign languages. But for this to happen, language-learning needs to make a comeback as a requirement of both primary and secondary education in the United States. Learning another language benefits each learner in at least three ways – pragmatically, neurologically and culturally.

He has some interesting reasons for urging us all to become polyglots.

Why can’t life begin after 40 for a writer?

Fiona Gartland, a journalist with The Irish Times for 13 years and newly published novelist, addresses the issue of ageism in publishing. Most publishers, she says, expect writers to have published a book by about the age of 40.

English author Joanna Walsh, who runs @Read_Women, has argued that ageism in publishing silences minorities and women in particular because women are more likely to be the ones who spend part of their lives caring for children, which makes finding time to write more difficult. She says “older women are already told every day in ways ranging from the subtle to the blatant, that they are irrelevant and should shut up”. Placing age barriers, for example for writing awards, is arbitrary and “a particularly cruel irony” for those unable to write in their youth, she says.

But “Not everyone finds a voice in their youth,” Gartland argues, and that “doesn’t mean what they have to say is any less valuable or any less worthy of hearing.”

Milkman is a bold choice but it’s unlikely to please booksellers

A consistent outsider in the bookies’ odds, Anna Burns’s Milkman is the sort of boldly experimental – and frankly brain-kneading – novel that is usually let in at longlist stage and gently dropped as the competition narrows. And for that reason alone it is a smartly provocative choice – one that has been waiting to be made as the publishing industry searches for the soul of its next generation.

Claire Armitstead writes in The Guardian that Anna Burns’s novel Milkman, winner of the Booker Prize, will challenge both bookstores and readers. Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, the novel features an 18-year-old narrator with a “relentlessly internalised” narrative that portrays “a social dysfunction that is both gothic and comically Kafkaesque.”

Milkman, Armitstead writes, is a novel that speaks “to political anxieties over hard borders in Ireland and around the more recently troubled world.”

Good Minds Suggest: Kate Morton’s Novels With Memorable Houses

Kate Morton’s latest novel, The Clockmaker’s Daughter, involves an old house and a secret hidden away there for 150 years. “Goodreads asked Morton to recommend her favorite novels where a house is nearly a central character in the story.” (See 6 Illustrations of How Setting Works in Literature.)

The use of place as an integral part of a story can add psychological depth to a novel. See what five novels Morton includes on her list.

© 2018 by Mary Daniels Brown