ARE WE ALL GASLIGHTERS?

How Crime Fiction Helps Us Understand The Part Communities Play in Continuing Abuse

The psychological concept of gaslighting takes its name from the film Gaslight starring Ingrid Bergman:

Gaslighting is a common aspect of abusive relationships, both in fiction and in real life. An abuser uses a variety of methods to keep the victim confused and off-balance. Some tactics come straight out of the old movie, just updated for modern technology. Abusers are using internet-connected speakers and thermostats to suddenly blast music at their victims, or to abruptly and invisibly raise or lower the temperature. They use phones and computers to spy on them.

Author Sarah Zettel explains exactly how the process of gaslighting works. She argues that society prepares us for this process:

Women are primed for gaslighting at an early age. When a little boy taunts a little girl, or punches her, or pulls her hair to make her cry, she’s told things like: He doesn’t really mean to hurt you. He just wants your attention. You should be nice to him.

…

So, she learns to doubt her judgment, and she learns that when she’s in trouble, she’s the one who has to work to make it better. Alone.

This is why gaslighting forms the basis for so many psychological thrillers. Zettel looks at Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins, and The Woman in the Window by A.J. Finn, among other books and films, as examples.

Should we stop reading into authors’ lives and get back to their books?

There are so many good writers whose politics and opinions leave us queasy about enjoying their work, though more would object to VS Naipaul than Charles Dickens. But is a story also a celebration of its author?

Author Nell Stevens considers this topic in light of the recent brouhaha raised by the death of V.S. Naipaul. I had my own similar crisis several years ago when the conservatively religious author Orson Scott Card went public with disparaging remarks about homosexuality, gay men, and lesbians. As much as I love Card’s novels Ender’s Game and Lost Boys, I finally decided that I could no longer support in any way someone who makes such remarks. I therefore have not bought or even borrowed from the library any works by Orson Scott Card.

Author Nell Stevens considers this topic in light of the recent brouhaha raised by the death of V.S. Naipaul. I had my own similar crisis several years ago when the conservatively religious author Orson Scott Card went public with disparaging remarks about homosexuality, gay men, and lesbians. As much as I love Card’s novels Ender’s Game and Lost Boys, I finally decided that I could no longer support in any way someone who makes such remarks. I therefore have not bought or even borrowed from the library any works by Orson Scott Card.

This was a hard decision for me, because I believe he has as much right to his opinion as I have to mine. I also believe that a novel, as a completed work of art, has a life of its own, separate from the life of its creator. When I was younger, I probably would have decided differently. But now that I’m closer to the end of my life than to the beginning, I’ve begun to wonder what my life will have stood for once I’m gone. Now I feel that it’s important for me to stand up for what I believe and to draw a line in the sand that demonstrates my commitment.

How about you? Where do you stand on this question?

How to Find the Perfect Book Genre For You

Like me, you probably already know what type of book you most like to read, but I found here some suggestions for reading outside my comfort zone as well. Have a look at some of the “if you liked ________, you might also like ______” comparisons for either more of what you like or something new to try.

14 of the Very Best Books Published in the 1970s, From Le Guin to Haley

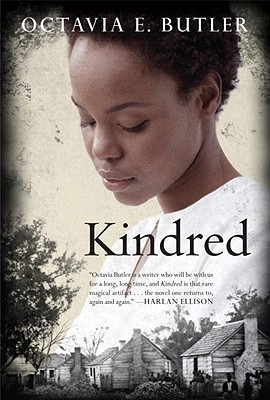

Having come of age in the glorious 1960s, I took particular interest in this list of books published in the following decade that, in a literary way, reflect the profound ways in which the ’60s influenced later society. The books from this list that I remember most vividly are Rabbit Redux by John Updike, Kindred by Olivia E. Butler, The Stories of John Cheever, All the President’s Men by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and Helter Skelter by Vincent Bugliosi.

Having come of age in the glorious 1960s, I took particular interest in this list of books published in the following decade that, in a literary way, reflect the profound ways in which the ’60s influenced later society. The books from this list that I remember most vividly are Rabbit Redux by John Updike, Kindred by Olivia E. Butler, The Stories of John Cheever, All the President’s Men by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and Helter Skelter by Vincent Bugliosi.

What about you? Do you remember any of these books?

All woman: the utopian feminism of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Perkins Gilman is best known for her famous 1892 short story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” in which a woman, confined to bed by the conventions of patriarchal Victorian conventions, grows increasingly insane. Here Michael Robertson, professor of English at The College of New Jersey, explains that Gilman “ended it as a writer of her own utopian fictions, including Herland (1915), a playful novel about an ideal all-female society.”

Despite Herland_’s time-bound shortcomings, we need its vision of a society without poverty and war, where every child is precious and inequalities of income, housing, education and justice are nonexistent. For all its faults, Herland_ remains an eloquent expression of the nonviolent democratic socialist imagination. As fully as any work in the utopian tradition, Herland reminds us of the truth of Oscar Wilde’s aphorism: ‘A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.’

© 2018 by Mary Daniels Brown