In celebration of Father’s Day, here are five memoirs about fathers.

The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr

Mary Karr describes a dysfunctional childhood—by turns hilarious and appalling—in an east Texas oil town. The book’s title comes from her father’s group of male friends who would assemble in the evenings to drink and see who could tell the tallest tale. Yet, despite her father’s drinking and her mother’s chaotic life fraught with secrets that eventually fractured the family, Karr avoids bitterness and anger by finding the humanity, or at least the humor, in most situations. She is primarily a poet, and her skill with language shines throughout her story. When my library book group read this many years ago, one woman said, “I wish we didn’t have to know about such a horrible childhood.” But I hold the opposite view: It’s important for us to read about such situations so that, as a society, we can understand and learn how to mitigate them.

Mary Karr describes a dysfunctional childhood—by turns hilarious and appalling—in an east Texas oil town. The book’s title comes from her father’s group of male friends who would assemble in the evenings to drink and see who could tell the tallest tale. Yet, despite her father’s drinking and her mother’s chaotic life fraught with secrets that eventually fractured the family, Karr avoids bitterness and anger by finding the humanity, or at least the humor, in most situations. She is primarily a poet, and her skill with language shines throughout her story. When my library book group read this many years ago, one woman said, “I wish we didn’t have to know about such a horrible childhood.” But I hold the opposite view: It’s important for us to read about such situations so that, as a society, we can understand and learn how to mitigate them.

When this book was first published in 1995, it helped usher in and nurture the reading public’s fascination with memoirs. The book description on Goodreads states that later editions of the book contain a new introduction about the book’s impact on Karr’s family. I’ll have to check the library, because that’s a topic that I, and a lot of other memoir writers and readers, would love to hear more about.

Gated Grief by Leila Levinson

As she was growing up, Levinson wondered why her father, a World War II veteran, often suffered from bouts of depression accompanied by outbursts of anger. Sometimes he could be a loving, caring father, but he became a different person during those times. To understand her father’s behavior she researched his war experiences and eventually learned of the atrocities he had witnessed in Europe during the war.

As she was growing up, Levinson wondered why her father, a World War II veteran, often suffered from bouts of depression accompanied by outbursts of anger. Sometimes he could be a loving, caring father, but he became a different person during those times. To understand her father’s behavior she researched his war experiences and eventually learned of the atrocities he had witnessed in Europe during the war.

I read Levinson’s book with interest because, when it came out, I had begun exploring my own father’s life. He had joined the Navy in 1941 at the age of 17. I was born a few years after he returned from the war. He committed suicide at age 36. I don’t have many memories of him and nobody talked to me (I was not quite 12) when he died, but from what I can determine, I think he must have come home with a bad case of what we now call PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). I think Leila Levinson and I both saw first-hand what often happens to soldiers who have lived through the horrors of war.

The Shadow Man by Mary Gordon

Gordon’s father died when she was seven years old. Her vague memories led her to think of him as the Shadow Man. In those memories he was a loving father, a charming intellectual, a writer and publisher, a Harvard dropout who led a bohemian existence during the Jazz Age. But well into her adulthood she longed to know more about him and began researching his life.

Gordon’s father died when she was seven years old. Her vague memories led her to think of him as the Shadow Man. In those memories he was a loving father, a charming intellectual, a writer and publisher, a Harvard dropout who led a bohemian existence during the Jazz Age. But well into her adulthood she longed to know more about him and began researching his life.

What she discovered shocked her to the core. In addition to being the loving father she vaguely remembered, she found out that he had also lied about all aspects of his life, even his place and date of birth. He was born to a Jewish family at the end of the nineteenth century but later converted to Catholicism and became outspokenly anti-Semitic. He openly supported right-wing politics and became a literary critic who also wrote pornography. The term Shadow Man takes an ironic twist as Gordon examines how his lies about his—and her—heritage had shaped and defined her own sense of self.

The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls

This is another memoir of children who grew up in a wildly dysfunctional family. The father captured his children’s imaginations with the wonders of science when he was sober, but when he drank he became desperate and destructive. The mother suffered from mental illness and refused to accept the responsibilities of parenthood. The children learned how to look after themselves and each other and eventually landed in New York City. Their parents later followed them there, where they chose to live as homeless people despite their children’s more settled lives.

This is another memoir of children who grew up in a wildly dysfunctional family. The father captured his children’s imaginations with the wonders of science when he was sober, but when he drank he became desperate and destructive. The mother suffered from mental illness and refused to accept the responsibilities of parenthood. The children learned how to look after themselves and each other and eventually landed in New York City. Their parents later followed them there, where they chose to live as homeless people despite their children’s more settled lives.

Despite their childhood, this is a remarkable tale of family and resilience that is often compared to The Liars’ Club because both books share a similar tone. It is heartening to see the successful lives the adult Walls children have created for themselves after living through such a childhood.

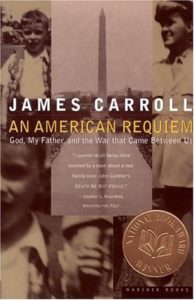

An American Requiem by James Carroll

During the 1950s and 1960s Carroll’s father rose through the ranks of the FBI and the Air Force to become coordinator of military intelligence. Carroll entered seminary and was ordained as a Catholic priest, while his brother joined the FBI. James became increasingly disillusioned with American involvement in Vietnam and became an outright protester against the war that his father so actively advanced. James eventually left the priesthood, but his political differences with his father caused a rift that was never repaired before the elder Carroll’s death.

During the 1950s and 1960s Carroll’s father rose through the ranks of the FBI and the Air Force to become coordinator of military intelligence. Carroll entered seminary and was ordained as a Catholic priest, while his brother joined the FBI. James became increasingly disillusioned with American involvement in Vietnam and became an outright protester against the war that his father so actively advanced. James eventually left the priesthood, but his political differences with his father caused a rift that was never repaired before the elder Carroll’s death.

I was drawn to this memoir because I knew James Carroll slightly when he was a Catholic chaplain during my senior year at Boston University. This account contains more history and politics than I usually like in a memoir, but in this case that information is all necessary to understand Carroll’s personal journey. I was surprised to see a number of comments on Goodreads saying that the book comes off as self-serving and self-aggrandizing. I didn’t know Jim Carroll very well, but I knew him well enough to know that the deep soul-searching in this memoir is genuine. This book well illustrates the function of memoir as a method of self-discovery and personal growth.

© 2017 by Mary Daniels Brown