Capote, Truman. “The Headless Hawk” (1945)

Capote, Truman. “The Headless Hawk” (1945)

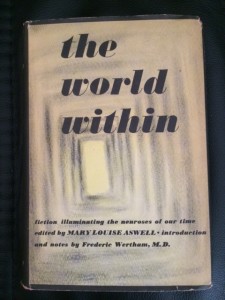

In The World Within: Fiction Illuminating Neuroses of Our Time

Edited by Mary Louise Aswell

Notes and Introduction by Frederic Wertham, M.D.

New York: Whittlesey House, 1947

Related Posts:

- “The World Within”: Introduction

- “Silent Snow, Secret Snow,” Conrad Aiken

- “The Door,” E.B. White

- “I Am Lazarus,” Anna Kavan

This story first appeared in Harper’s Bazaar in October 1945. It later appeared in the collection A Tree of Night and Other Stories (1949) and in The Complete Stories of Truman Capote (2005).

In her introduction to the story, Mary Louise Aswell, literary editor of The World Within, wrote that Capote, then in his 20s, had “consistently explored a territory of the mind that our generation knows instinctively, but dimly.” She added that “we ourselves have visited it in the dark” and are moved to “the catharsis at least of terror” (p. 283). In an interview published in the spring-summer 1957 issue of The Paris Review, Capote acknowledged Mary Louise Aswell of Harper’s Bazaar as one of the editors who most encouraged him early in his career.

Truman Capote later became known for his innovative writing style in In Cold Blood, but in his early stories of the 1940s he was a master at using gothic elements to create psychological states. He is therefore often associated with the Southern gothic tradition of writers such as Carson McCullers, Eudora Welty, and William Faulkner.

In “The Headless Hawk,” Vincent, a 36-year-old art gallery employee in Manhattan, has an affair with a young girl, who remains mysteriously unnamed, who sells him a painting depicting a girl with a severed head and a large, headless hawk. Both the painting and the girl draw Vincent in in a way that first thrills, then repulses him.

The story opens with the following quotation from the biblical book of Job:

They are of those that rebel against the light; they know not the ways thereof, nor abide in the paths thereof. In the dark they dig through houses, which they had marked for themselves in the daytime: they know not the light. For the morning is to them as the shadow of death: if one know them, they are in the terrors of the shadow of death.

—Job 24:13, 16, 17

Capote uses imagery to create an atmosphere of darkness and death in keeping with this epigraph. We first meet Vincent when a “promise of rain had darkened the day since dawn” (p. 284). He lives in a dark basement apartment. Much of the story’s action takes place either under cloud-darkened skies or at night. Scenes, such as Vincent’s stumbling, rambling visit to a Broadway funhouse and penny arcade, become surreal night visions. Other macabre scenes come to Vincent in dreams.

Imagery of the sea, of submersion, also creates a picture of Vincent moving unnaturally through the world, encumbered in an alternate reality: “Vincent felt as though he moved below the sea” (p. 284). Buses “seemed like green-bellied fish, and faces loomed and rocked like wave-riding masks” (p. 284). Vincent sees himself in a dream “swimming through oceans of cheese-pale faces, neon, and darkness” (p. 293). Later, “The air seemed thick with gummy fluid” (p. 307).

Vincent is out of sync with the world, “never quite in contact, never sure whether a step would take him backward or forward, up or down” (p. 284). He had “substituted for a sense of a reality a knowledge of time, and place” (p. 287). Later, Vincent thinks of himself as “a man in the sea fifty miles from shore” (p. 291).

Narrative structure also contributes to the creation of a dark, foreboding, otherworldly atmosphere. In the opening section of the story, Vincent sees the girl and tries to elude her. But he watches where she goes and then approaches her. He stops to light a cigarette in front of her, and she steps out of the shadows and offers her lighter. This action sequence is disconcerting for the reader because it seems counterintuitive: Who is stalking whom? He walks away, and she wanders into traffic, causing a cab driver to yell. Vincent turns and sees her staring straight at him, “trance-eyed, undisturbed as a sleepwalker” (p. 286). He walks on but continues to hear “the soft insistent slap of [her] sandals” (p. 286).

Much of the rest of the story is an extended flashback about how Vincent and the girl met and how their relationship developed. Events jump back and forth in time as the flashback unfolds, and this disjointed time sequence contributes to the story’s sense of jumbled reality.

The focal point of the story is the girl’s painting, with its dominant image: “The wings of a hawk, headless, scarlet-breasted, copper-clawed, curtained the background like a nightfall sky” (p. 289). For Vincent, the painting, though lacking technical merit, “had that power often seen in something deeply felt, though primitively conveyed” (p. 289). He just knows that he must have the painting, which has “revealed to him a secret concerning himself” (p. 290). On nights when he can’t sleep, “he would pour a glass of whiskey and talk to the headless hawk, tell it the stuff of his life” (p. 291). At those times he sees himself as “someone … without direction, and quite headless” (p. 291).

Vincent sees himself in the headless hawk: “a victim, born to be murdered, either by himself or another; an actor unemployed. It was there, all of it, in the painting, everything disconnected and cockeyed, and who was she that she should know so much?” (p. 291). It is this question that piques his interest in the girl:

There are certain works of art which excite more interest in their creators than in what they have created, usually because in this kind of work one is able to identify something which has until that instant seemed a private inexpressible perception, and you wonder: who is this that knows me, and how? (p. 290)

The climax of the story comes in a dream in which a young and handsome Vincent recognizes an “old and horrid” (p. 302) Vincent. Of other guests in the room of his dream, “many are also saddled with malevolent semblances of themselves, outward embodiments of inner decay” (p. 302). In the dream a man approaches with “a massive headless hawk whose talons, latched to the wrist, draw blood” (p. 302).

After this dream, Vincent realizes that

he’d betrayed himself with talents unexploited, voyages never taken, promises unfulfilled … oh why in his lovers must he always find the broken image of himself? Now as he looked at her in the aging dawn his heart was cold with the death of love (p. 304).

He gathers the girl’s belongings and puts them and her out, marking the death of yet another love, just as all his other love affairs have ended. The phrase “the death of love” recalls the epigraph’s references to the shadow of death.

In his brief remarks after the story, psychiatrist Frederic Wertham focuses on the girl, whom he describes as a schizophrenic portrayed with “almost clinical accuracy” (p. 311). Wertham also touches on the story’s “surrealist tapestry” of “phosphorescent decadence” (p. 311), but about Vincent, the story’s protagonist, he has little to say.

The psychiatrist’s remarks don’t do the story justice and in fact demonstrate how we understand the human psyche as portrayed in literature. We don’t need a clinical diagnosis of a specific condition, complete with a catalog of symptoms. Rather, we more often experience psychological states in literature as a “private inexpressible perception,” a “territory of the mind that our generation knows instinctively, but dimly,” that we may not know how to articulate ourselves but recognize when we see represented by an artist of words.

In fact, this story well illustrates how that process works. Capote’s language creates more of an atmosphere than coherent symbolism. Even the headless hawk produces a general, though macabre, feeling of terror and unreality that cannot be mapped as a specific symbol (e.g., headless hawk = death, headless hawk = fear). This story well illustrates how a master of language such as Truman Capote can communicate psychological truth that feels more real to readers than a clinical description would.

© 2015 by Mary Daniels Brown