Related Posts:

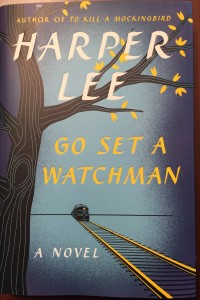

- Review: “Go Set a Watchman”

- Compendium on “Go Set a Watchman”

- More on Harper Lee’s “Go Set a Watchman”

Lee, Harper. Go Set a Watchman

New York: HarperCollins, 2015

ISBN 978–0–06–240985–0

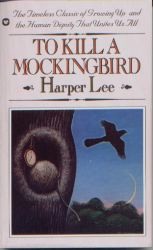

Consensus is that Go Set a Watchman is the manuscript that Harper Lee originally submitted to publisher J. B. Lippincott Company in 1957. Editor Therese von Hohoff Torrey, known as Tay Hohoff, deemed the novel not ready for publication, but she saw potential in the story. For two years Hohoff and Lee worked on revising the manuscript, which eventually evolved into To Kill a Mockingbird, published in 1960. (Harper & Row bought Lippincott in 1978. Harper & Row eventually became HarperCollins, the publisher of Watchman.)

A comparison of Watchman and Mockingbird as literary works provides a lesson for both writers and readers in how fiction works.

Telling, Not Showing

The most common piece of advice offered to aspiring novelists is “show, don’t tell.” This means that the work must demonstrate characters’ qualities, not simply state them. Here’s a made-up example of telling:

Joe and his wife Mabel sit across from each other at the kitchen table. Joe is angry with Mabel because she told him he needed to get a job right away.

Here’s how showing works to communicate Joe’s state of mind:

Joe and his wife Mabel sit across from each other at the kitchen table. Joe pounds his fist on the table as he leans in toward Mabel. “Nothing I do is ever good enough for you, is it?” he hisses. “Do you have any idea how that makes me feel? I’d like to be able to count on a little support from you instead of just constant criticism.”

When a writer simply states that Joe is angry, readers are passive recipients of that information. But when a writer shows Joe acting with anger, readers participate in receiving that information by evaluating Joe’s behavior to understand it. Showing rather than telling engages readers by making them active participants in the reading experience.

Watchman does a lot more telling than showing. Here, for example, is the narrator telling us about the character of Atticus Finch:

Integrity, humor, and patience were the three words for Atticus Finch… . Atticus Finch’s secret of living was so simple it was deeply complex: where most men had codes and tried to live up to them, Atticus lived his to the letter with no fuss, no fanfare, and no soul-searching. His private character was his public character. His code was simple New Testament ethic, its rewards were the respect and devotion of all who knew him. (p. 124)

Compare this characterization with the one we receive in Mockingbird by hearing Atticus Finch defend Tom Robinson at trial and, later, by seeing him spend the night at the jail to protect his client from an angry mob. Those scenes make readers themselves respect Atticus Finch by demonstrating his character instead of just telling readers that other people respect him.

Narrative Structure

Narrative structure (see narrative with plot) is the order in which novelists reveal key events in relation to the times at which those events occurred. When authors need to present something that happened earlier than the novel’s present, they use flashbacks.

In the present time of Watchman, Jean Louise Finch is 26 years old. There are several times in the novel when she remembers events from her childhood, such as when she, her brother Jem, and their summer neighbor Dill used to play Tom Swift. These flashbacks engage readers by allowing them to observe the children directly, without the intrusion of a narrator telling readers what to think or believe. Because the flashbacks allow such direct observation, they are more interesting than anything that happens in the novel’s present time.

These flashbacks, which show rather than tell, contrast sharply with the predominantly plodding prose of the novel’s present. But they don’t have much to do with the rest of the novel. They do not help move the action of the present forward, and they do not resonate with other themes in the novel except, perhaps, in creating a general atmosphere of nostalgia.

Finding the Story’s Center

The flashbacks that feature the novel’s most engaging writing are the first indication of where the center of the real story lies: in Jean Louise’s childhood. This shift in time from Jean Louise’s adulthood in Watchman to Scout’s childhood in Mockingbird is the most significant—and the most effective—change from the earlier manuscript to the later novel.

Once the focus of the story changes from a 26-year-old Jean Louise to a six-year-old Scout, the moment of revelation must also change. In Watchman Jean Louise has her epiphany while spying on Atticus at a political meeting from the balcony of the county courthouse. Mockingbird retains the courthouse balcony setting but must change the nature of the revelation. Whereas the older Jean Louise observes what she considers her father’s hypocrisy, Scout and Jem realize the outstanding character of the father who had before seemed simply ordinary to them.

The Result

Relocating the center of the story to the children’s realization of their father’s courage and strength of character is what makes Mockingbird an essentially different book than Watchman. This is one reason why it is not necessary to reconcile the Atticus of Watchman with the Atticus of Mockingbird.

Relocating the center of the story to the children’s realization of their father’s courage and strength of character is what makes Mockingbird an essentially different book than Watchman. This is one reason why it is not necessary to reconcile the Atticus of Watchman with the Atticus of Mockingbird.

A second reason is that what we are dealing with is fiction. Watchman and Mockingbird are two different books. They are allowed to have different characters. Atticus Finch is not a real person.

[tweetthis]As works of art, To Kill a Mockingbird is a better novel than Go Set a Watchman.[/tweetthis]Much of the discussion about Watchman has centered around whether Harper Lee was truly capable of agreeing to its publication. We may never know. But of one thing I am sure: Judged solely as works of art, To Kill a Mockingbird is a better novel than Go Set a Watchman. Looking at the two side by side provides a good picture for both writers and readers of how effective fiction works.