The 6 types of Little Free Library patrons

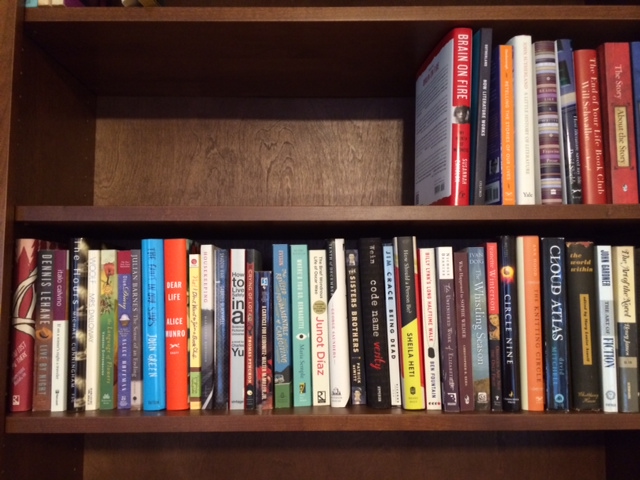

Mary Ann Gwinn, book editor for The Seattle Times, receives LOTS of books. As a way to spread the wealth around, her spouse built her a Little Free Library for her birthday.

The Little Free Library movement was started in Wisconsin by Todd Bol and Rick Brooks in 2009. Its mission is two-fold:

- To promote literacy and the love of reading by building free book exchanges worldwide.

- To build a sense of community as we share skills, creativity and wisdom across generations.

Its goal is “To build 2,510 Little Free Libraries—as many as Andrew Carnegie.”

This goal was reached in August of 2012, a year and a half before our original target date. By January of 2015, the total number of registered Little Free Libraries in the world was conservatively estimated to be nearly 25,000, with thousands more being built.

The philosophy behind little free libraries is “Take a book. Return a book.” In other words, for every book you take, you should put one book back. The aim of the process is to promote not only general literacy, but also neighborhood community. These libraries are run on the honor system by community members, for each other.

In addition to allowing Gwinn to share her books, the Little Free Library provides “an added benefit: … a fantastic opportunity for people-watching.” Read her descriptions of these patrons of her LFL:

- The busy mom

- The insomniac

- The wannabe book critic

- The picky reader

- The cruiser

- The grateful recipient

I like her observation that “The key to having a Little Free Library is to release control.” Since patrons put in one book for every book they take out, “You can control the outbox, but you can’t control the inbox.”

Gwinn is certainly experiencing the community intent of the Little Free Library philosophy: “That is the gift of the Little Free Library; you get to know your neighbors, in all sorts of ways.”

In a Mother’s Library, Bound in Spirit and in Print

New York Times technology writer Nick Bilton describes how books became a bond and a form of communication between himself and his mother:

As I grew up, my mother held my hand as we wandered through the fictional worlds of Harper Lee, Charles Dickens and Lewis Carroll. Birthdays and Christmases were always met with rectangular-shaped gifts.

As he got older, he and his mother spend hours discussing plots and characters.

But in 2011, Bilton and his mother got into an argument over books. When he was moving from New York to California, he decided to leave behind most of his books in favor of a Kindle and later an iPad. His mother was appalled:

She spoke passionately about being able to smell the pages of a print book as you read, to feel the edges of a hardcover in your hands. And that the notes left inside by the previous reader (often my mother) could pause time.

After his mother died in March, Bilton and his two sisters learned that she had left her collection of more than 3,000 books to her oldest daughter. Knowing the bond that books had created between Bilton and their mother, his sister offered to share their mother’s library with him, and he “gratefully accepted.”

As a technology writer, Bilton had spent much time discussing the merits of print vs. digital books. But his mother’s death and his receipt of some of her books made him realize that one is not superior to the other: “They each have their place in this modern world.” He caps this realization with a description of how his mother, knowing she would not live long enough to meet Bilton’s unborn son, inscribed her copy of her favorite book, Alice in Wonderland, to him. That book, along with some of her others, sits in her grandson’s nursery, the basis of his own growing book collection.

As a technology writer, Bilton had spent much time discussing the merits of print vs. digital books. But his mother’s death and his receipt of some of her books made him realize that one is not superior to the other: “They each have their place in this modern world.” He caps this realization with a description of how his mother, knowing she would not live long enough to meet Bilton’s unborn son, inscribed her copy of her favorite book, Alice in Wonderland, to him. That book, along with some of her others, sits in her grandson’s nursery, the basis of his own growing book collection.