White, E.B. “The Door” (1939)

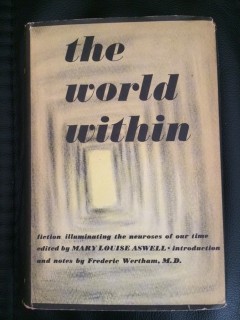

In The World Within: Fiction Illuminating Neuroses of Our Time

Edited by Mary Louise Aswell

Notes and Introduction by Frederic Wertham, M.D.

New York: Whittlesey House, 1947

Related Posts:

“The Door” originally appeared in The New Yorker in 1939. If you have a subscription with access to that magazine’s digital archives, you can read the story here. The text of “The Door” is available for free here.

“The Door” originally appeared in The New Yorker in 1939. If you have a subscription with access to that magazine’s digital archives, you can read the story here. The text of “The Door” is available for free here.

If you know E.B. White primarily as the author of the children’s classics Stuart Little and Charlotte’s Web, “The Door” will surprise you. In just a few short pages this story presents a picture of a man thinking about the upsetting novelty and inscrutability of an era marked by the political, societal, and philosophical upheavals of global war, an era that Aswell labeled “this age of freedom from certainty” (p. vii) in her introduction to The World Within.

The opening few sentences set the scene:

Everything (he kept saying) is something it isn’t. And everybody is always somewhere else. Maybe it was the city, being in the city, that made him feel how queer everything was and that it was something else. Maybe (he kept thinking) it was the names of the things. The names were tex and frequently koid. Or they were flex and oid or they were duroid (sani) or flexsan (duro)… . (p. 261).

The meaningless words (which have become much more common to today’s consumers than they were to White’s original audience) reinforce the sense of incomprehensibility of everything being something it isn’t and everybody always being somewhere else. The parenthetical phrases “(he kept saying)” and “(he kept thinking)” make us wonder who he is and who exactly is telling us about him.

Anyone who has ever taken an introductory psychology course will recognize the story’s dominant image: an experiment in which rats are trained to open a marked door behind which they have learned they’ll find food. It’s hard not to see this experiment as an allusion to modern life as a rat race (a term my dictionary tells me first appeared in 1939). After the rats have learned to jump at the marked door to obtain food, the experimenters remove the food to find out how long it will take the rats to unlearn what they had previously learned:

but then one day it would be a trick played on the rat, and the card would be changed, and the rat would jump but the card wouldn’t give way, and it was an impossible situation (for a rat) and the rat would go insane and into its eyes would come the unspeakable bright imploring look of the frustrated, and after the convulsions were over and the frantic racing around, then the passive stage would set in and the willingness to let anything be done to it, even if it was something else. (p. 262)

The result of this experimental manipulation is madness:

More and more (he kept saying) I am confronted by a problem which is incapable of solution (for this time even if he chose the right door, there would be no food behind it) and that is what madness is, and things seeming different from what they are. (pp. 262–263)

The life of the story’s anonymous subject has been a series of such manipulations. First the world taught him that religion was the appropriate approach:

First they would teach you the prayers and the Psalms, and that would be the right door… . Then one day you jumped and it didn’t give way, so that all you got was the bump on the nose, and the first bewilderment, the first young bewilderment. (pp. 263–264)

But he continued to follow society’s directives, turning next to love and marriage as the proper way, “the door with the picture of the girl on it … her arms outstretched in loveliness” (p. 265). For a while that door “was the way,” until they also changed that door on him:

although my heart has followed all my days something I cannot name, I am tired of the jumping and I do not know which way to go, Madam, and I am not even sure that I am not tried beyond the endurance of man (rat, if you will) and have taken leave of sanity. (p. 265)

Now this man-rat has “taken leave of sanity” and is facing “an impossible situation” (p. 262), “a problem which is incapable of solution” (p. 263). But he has no choice other than to keep on jumping:

and the thing is to get used to it and not let it unsettle the mind. But that would mean not jumping, and you can’t. Nobody can not jump. There will be no not-jumping. Among rats, perhaps, but among people never. Everybody has to keep jumping at a door (the one with the circle on it) because that is the way everybody is, specially some people. (pp. 264–265)

In addition to this image of the manipulative experiment, White uses changing point of view to communicate the protagonist’s fragmenting sense of self and loss of personal identity. The story begins in third person, “(he kept saying),” which then morphs into first person, “More and more (he kept saying) I am confronted by a problem which is incapable of solution” (pp. 262). This shift in point of view and the lack of quotation marks here in the text make readers begin to lose a sense of difference between the character—“he”—in the story and the narrator who is supposedly observing the character and telling readers about him. And the shift to second person—“they would always wait till you had learned to jump at the certain card (or door)—the one with the circle—and then they would change it on you” (p. 263)—creates the sense of universal inclusiveness. (We often use you like this in common speech, for example, “You have to walk before you can run.”) I, you, he: we’re all in this together.

In his endnote the psychiatrist Frederic Wertham calls this story “a tour de force in free association. I would rather call it ‘free dissociation’” (p. 268). He adds that the significance of the story lies “not in the description of a specific disease, not in the description of thought, but in the picture of thinking” (p. 268). E.B. White’s style, with its run-on sentences and seemingly random juxtapositions of wildly unrelated thoughts, underscores the picture of disjointed, illogical thought processes. As Wertham writes in his introduction to The World Within, “Great writers know how to give a unified picture of a whole personality through minute observation of a meaningful expression, a characteristic mannerism, or an unconscious habit” (p. xvi).