Aiken, Conrad. “Silent Snow, Secret Snow” (1934)

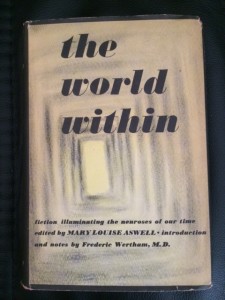

In The World Within: Fiction Illuminating Neuroses of Our Time

Edited by Mary Louise Aswell

Notes and Introduction by Frederic Wertham, M.D.

New York: Whittlesey House, 1947

Related Post:

I remember discovering this story in an anthology of American short stories back in high school. I found it absolutely chilling back then, and it hasn’t lost any of its power over the years. The story is widely anthologized, especially in collections of American short stories, so you should be able to find it with a bit of searching. Or you can look for The Collected Short Stories of Conrad Aiken, which is more difficult to find. This link will take you to Google Books, where you can search for the book in a library near you.

I remember discovering this story in an anthology of American short stories back in high school. I found it absolutely chilling back then, and it hasn’t lost any of its power over the years. The story is widely anthologized, especially in collections of American short stories, so you should be able to find it with a bit of searching. Or you can look for The Collected Short Stories of Conrad Aiken, which is more difficult to find. This link will take you to Google Books, where you can search for the book in a library near you.

How does an author write about something “which could not easily (if at all) be spoken of” (p. 244)? In this story Conrad Aiken literarily presents the process by which 12-year-old Paul Hasleman loses touch with reality and slips into a world of delusion. The delusion begins with Paul’s belief that snow has fallen outside and is muffling the postman’s footsteps, but when he looks outside, he sees bright sun and no snow on the street. Yet in his mind Paul sees snow: “this was distinctly pleasant, and came almost of its own accord” (p. 239). Paul instinctively knows that he must keep his vision of snow a secret from his parents, his schoolmates, and the family doctor whom his parents finally call in because Paul seems distracted and engages in extensive daydreaming.

Paul initially thinks of his secret as a treasure that he alone possesses. The secrecy gives his treasure a sense of deliciousness. The secret also gives him a sense of protection from the rest of the world. Soon Paul begins to recognize that he has “another and quite separate existence” (p. 243) from the world of his home and school. He differentiates between “the public life and the life that was secret” (p. 245) and recognizes “the increasing difficulty of the daily return to daily life” (p. 247).

Aiken was an accomplished poet, and in this story he uses poetic devices to portray Paul’s increasing alienation from reality. He uses visual imagery to demonstrate what Paul sees: “The little spiral was still there, still softly whirling, like the ghost of a white kitten chasing the ghost of a white tail, and making as it did so the faintest of whispers” (p. 256). Aiken also uses sound imagery; the heavy, recurring sibilance (s sound) throughout the story echoes what Paul hears. Here, for example, Paul is distracted while the doctor is examining him:

Even here, even amongst these hostile presences, and in this arranged light, he could see the snow, he could hear it—it was in the corners of the room, where the shadow was deepest, under the sofa, behind the half-opened door which led to the dining room. It was gentler here, softer, its seethe the quietest of whispers, as if, in deference to a drawing room, it had quite deliberately put on its “manners”; it kept itself out of sight, obliterated itself, but distinctly with an air of saying, “Ah, but just wait! Wait till we are alone together! Then I will begin to tell you something new! Something white! something cold! something sleepy! Something of cease, and peace, and the long bright curve of space! Tell them to go away. Banish them. Refuse to speak.” (p. 254)

The snowstorm that begins so seductively in Paul’s head turns savage by the story’s end:

The darkness was coming in long white waves. A prolonged sibilance filled the night—a great seamless seethe of wild influence went abruptly across it—a cold low humming shook the windows. He shut the door and flung off his clothes in the dark. The bare black floor was like a little raft tossed in waves of snow, almost overwhelmed, washed under whitely, up again, smothered in curled billows of feather. The snow was laughing: it spoke from all sides at once: it pressed closer to him as he ran and jumped exulting into his bed. (p. 258)

The oxymoron (seeming contradiction) of darkness coming in white waves emphasizes the break from reality as Paul listens to the snowstorm and his mind closes inward upon itself:

“Listen!” it said. “We’ll tell you the last, the most beautiful and secret story—shut your eyes—it is a very small story—a story that gets smaller and smaller—it comes inward instead of opening like a flower—it is a flower becoming a seed—a little cold seed—do you hear? we are leaning closer to you—“ (p. 259)

In her introduction to “Silent Snow, Secret Snow,” literary editor Aswell describes Aiken (1889-1973) as “one of the writers whose work first showed the specific influence of Freud” (p. 237). But readers need not know details of Freud’s theories to recognize the significance of Paul’s experience as Aiken portrays it. As psychiatrist Wertham says in his closing notes on the story, “The description is the better since it is free from cliches of symptoms” (p. 260).

© 2014 by Mary Daniels Brown