There’s been a lot in the news lately about a study suggesting that children do not gain accurate knowledge of the natural world by reading stories with human-like animals.

Dr. Patricia A. Ganea, of the psychology department at the University of Toronto, and colleagues examined how books that present animals with human characteristics (that is, animals that talk and think like humans) affect children’s learning about the natural world. Here’s the abstract of the research report published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology:

Do cavies talk?: The effect of anthropomorphic books on children’s knowledge about animals

Many books for young children present animals in fantastical and unrealistic ways, as wearing clothes, talking and engaging in human-like activities. This research examined whether anthropomorphism in children’s books affects children’s learning and conceptions of animals, by specifically assessing the impact of depictions (a bird wearing clothes and reading a book) and language (bird described as talking and as having human intentions). In Study 1, 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children saw picture books featuring realistic drawings of a novel animal. Half of the children also heard factual, realistic language, while the other half heard anthropomorphized language. In Study 2, we replicated the first study using anthropomorphic illustrations of real animals. The results show that the language used to describe animals in books has an effect on children’s tendency to attribute human-like traits to animals, and that anthropomorphic storybooks affect younger children’s learning of novel facts about animals. These results indicate that anthropomorphized animals in books may not only lead to less learning but also influence children’s conceptual knowledge of animals.

A release from the University of Toronto added:

“Books that portray animals realistically lead to more learning and more accurate biological understanding,” says lead author Patricia Ganea, Assistant Professor with the University of Toronto’s Department of Applied Psychology and Human Development. “We were surprised to find that even the older children in our study were sensitive to the anthropocentric portrayals of animals in the books and attributed more human characteristics to animals after being exposed to fantastical books than after being exposed to realistic books.”

Publication of this research has sparked some heated negative responses. In The Telegraph (a newspaper from the U. K.), mother Becky Pugh wrote “Don’t tell me talking animals like Peppa Pig are bad for my kids“:

Indeed, most of our furry humanoid favourites have wisdom to impart – even if their portrayal of the natural world isn’t always accurate. Rupert Bear encourages an adventurous spirit. Winnie the Pooh represents thoughtfulness, humility and companionship. Babar champions deference and respect for your elders. Paddington endorses courage and independence.

Katy Waldman, an assistant editor at Slate, entitled her article “Researchers Want Children’s Books to Stop Anthropomorphizing Animals. That’s a Terrible Idea.” Waldman insists:

Scaffolding familiar traits onto alien subjects is a powerful way to promote learning, one that children do naturally from the age of 12 to 24 months. And imaginative play—the type where you pretend a badger gets jealous of her baby sister—has cognitive benefits: “If you want your children to be intelligent,” Albert Einstein once said, “read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” Just as important, anthropomorphizing is a type of metaphor-making that allows kids to both identify with the characters they’re reading about (so that they more readily apply the text’s lessons to their own life, as in an Aesop’s fable) and practice acknowledging outside perspectives. Reading literature fosters empathy, found two separate studies, one at the New School and one in the Netherlands, and it does so by awakening people to the echoes of themselves in others.

Ganea addressed all the negative publicity in an interview with Cathy Newman for National Geographic:

Your work seems to have struck a negative nerve. “Stop reading Jungle Book and Winnie The Pooh as it ‘humanises animals’, parents told,” was one headline I saw in the London Daily Express. There were others.

People have gone crazy out there. They think we are saying, don’t read books that interweave fantasy with reality. That’s not the message from this. It’s if you want your children to learn more facts about animals, it would be better to use books that are more realistic. Of course parents should read a variety of books to their children. Fantasy is important for their imagination and their cognitive development.

Ganea said that she enjoyed Winnie the Pooh with her own children. “But we also read expository books about animals.”

Other people have been more receptive to Ganea’s message. In the Canadian paper The Globe and Mail, parent Tralee Pearce wrote, “Why you may want to stop reading bedtime stories with cartoony, human-like animals.” She acknowledged that she “may consider adding in a hard-core nature book or two” to her children’s reading list:

This might be even more crucial to consider, as another study found that the use of the outdoors and animals in children’s literature has been on the decline since the 1970s; as more kids are raised in urban landscapes, their books come to reflect that reality.

Maybe this is all a (sad) reflection of our general disengagement with the natural world – and a reminder to parents and educators to sneak in some information about real animals into story time at home and school.

And on the Scientific American blog “The Thoughtful Animal,” developmental psychologist Dr. Jason G. Goldman titled his post “When Animals Act Like People in Stories, Kids Can’t Learn.” Goldman wrote:

The problem is actually more pervasive than it sounds: human adults, at least in the US, are also highly likely to imbue non-human animals with human-like emotions and motivations. It’s a tricky line to navigate. Research is increasingly revealing the fundamental similarities between our species and the rest of the animal kingdom, but there are also aspects of human culture that are, indeed, unique to our species. Is it reasonable to suggest that an animal can feel something complex like pride or embarrassment? We are poised to attribute a similarly complex emotion, guilt, to dogs, but a deeper look reveals that while dogs indeed have a “guilty look,” they probably do not actually realize that they’ve transgressed. If children are routinely exposed to these sorts of anthropomorphic representations of animals, it is no wonder that they grow up to become adults who look at non-human animals as if they are people wearing animal suits.

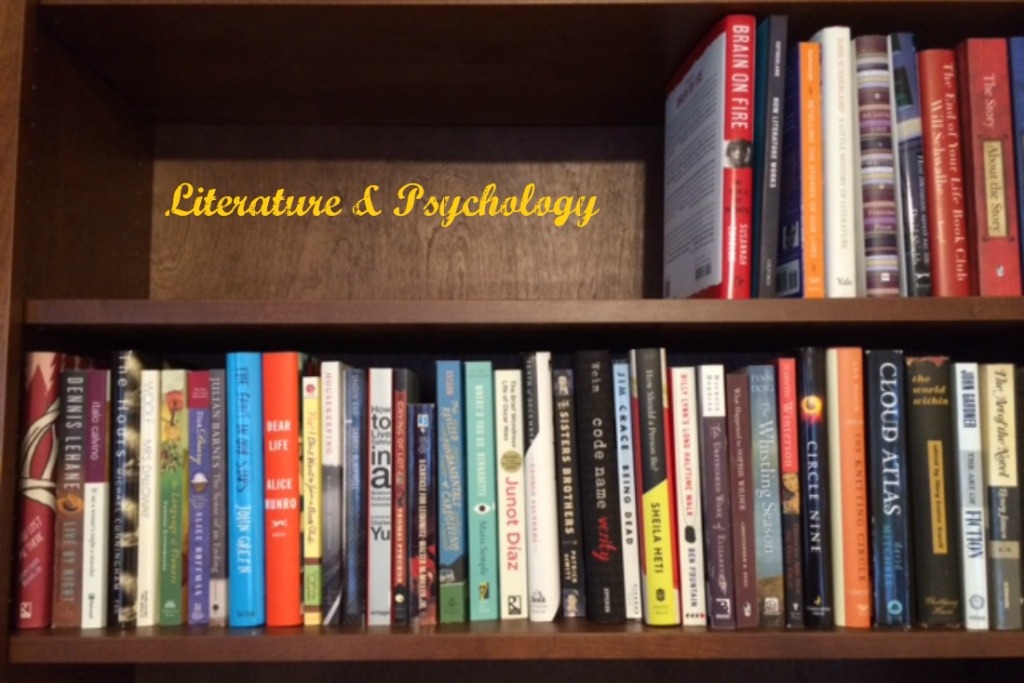

He added that this research “presents an opportunity for parents and teachers to carefully select books that do accurately reflect the natural world, both visually and linguistically.” And he concluded that books representing the worlds of both fantasy and reality can co-exist. “Maybe let’s just keep them on different shelves?”