17 Most Screwed Up Relationships In Books

From Oedipus and Jocasta to Anastasia and Christian Grey, here are the most dysfunctional book couples. Trust us, these people will make you feel good about your worst relationship.

To which list I would add those kids from Flowers in the Attic.

20 Of The Biggest Dick Moves In Literature

I can’t make this stuff up. I just don’t think this way. But I’m glad that other people do, because often even the wackiest sounding list has some kernel of insight behind it.

This one, which covers literature from Homer’s Odyssey to the Harry Potter series, is a case in point:

WARNING: Spoilers. Because as we all know, authors can be jerks and their characters even more so.

Psychopaths in Fact, Fiction, and Your Everyday Life

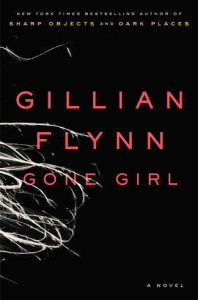

They’re the characters we love to hate: from Shakespeare’s Iago in Othello and both Amy and Nick in Gone Girl in literature to television’s Walter White in Breaking Bad and Dexter Morgan in Dexter. They’re the villains, characters we’ve come to call “psychopaths” through the influence of contemporary literature, movies, and television:

The great popular psychopathic characters of fiction are more than mere psychopaths. They exhibit other shades of the “dark triad”: Machiavellianism (exploiting others) and narcissism (extreme self-centeredness). Although in real life, narcissists are perceived more favorably than people high in the other two dark triad qualities (Rauthmann & Kolar, 2013), the darker the fictional anti-hero, the more we are compelled to watch him or her at work. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung proposed that we each carry an image (or archetype) of the hero deep in our unconscious roots. Fictional heroes resonate with this deep-seated longing we have to admire the epitome of honor and goodness. The anti-hero draws us into a similarly powerful vortex through the shadow archetype which personifies pure evil.

Psychology professor Susan Krauss Whitbourne looks at why we find these characters so eternally appealing.

The grandmothers of “Gone Girl”

Few people know more about crime fiction than Sarah Weinman, a publishing journalist and critic who specializes in searching out and celebrating the best novels of mischief and mayhem. (Just this year she’s pointed me to such artful page-turners as A.S.A. Harrison’s “The Silent Wife” and Kelly Braffet’s “Save Yourself.”) Now Weinman has edited an anthology of her own, “Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories From the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense,” which collects short stories by a lost generation of women. These writers spun unsettling tales set in kitchens and bedrooms, where the tension grows out of our closest — and most dangerous — relationships. A couple of them, Patricia Highsmith and Shirley Jackson, have held onto their followings, but the rest, despite their past popularity, are in danger of vanishing from memory. These are the predecessors of such psychologically probing crime novelists as Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn, and thanks to Weinman, they’re poised to reach a bumper crop of new readers.

Here’s a fascinating look at the mystery subgenre of domestic suspense. Read about why many of these women writers, who were popular in their own time, have been nearly forgotten while their male contemporaries have entered the literary canon.

Women Vs Thrillers

If Sarah Weinman wonders why women have lost recognition as suspense writers, writer Susi Holliday also wonders why women have stereotypically been cut from the thriller genre:

But apparently, women are not supposed to like action thrillers – we’re meant to like more cerebral, “psychological” type stories about families and lovers and the trials of being a mother/single/fat* (*delete where applicable). Agatha Christie has never been described as a writer of “action thrillers”. We women need to read about characters who have brains, not just brawn…

She concludes, “Personally, I like a burst of brainless adrenalin as much as the next (wo)man. As long as there’s a ball-breaking female in there to keep the boys in check.”

On The Pleasures and Solitudes of Quiet Books

This article caught my eye because I recently described Plainsong by Kent Haruf as a quiet book. By quiet I meant something like low-keyed, not explosive or thunderous, but simply, easily, and elegantly meaningful.

Here Emily St. John Mandel explains, much more eloquently, how she defines a quiet book:

Any definition of what constitutes a quiet book will naturally be subjective, but I think the important point here is that quiet isn’t the same thing as inert. I’m not talking about the tediously self-conscious novels written by authors who use “literary fiction” as a sort of alibi, as in “my book doesn’t have a plot, because it’s literary fiction.” I rarely get more than fifty pages into these books before they join the books-that-need-to-get-out-of-my-apartment-immediately pile by the front door. Nor is quiet necessarily the same thing as minimalist. Raymond Chandler’s prose is minimalistic, but his stories aren’t quiet. The books I think of as being quiet, the ones I’ve been enjoying lately, have a distilled quality about them, an unshowy thoughtfulness and a sense of grace, of having been boiled down to the bare essentials.

She concludes with a list of six books (none of which is Plainsong) that she considers exemplify her definition. Her descriptions of these books make me think that her definition and mine are pretty similar. And another book I’d add to the list is John McGahern’s By the Lake.