Hogwarts Is in Your Head, Harry: Conspiracy Theories About Literature

Emily Temple weighs in over at The Atlantic:

Sherlock Holmes and Watson are lovers, Winnie the Pooh is a mental-illness allegory, and other theories that might forever alter your favorite books.

There was a pretty fascinating article over at Salon earlier this month, in which Greg Olear argues that Nick Carraway, the narrator of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, was gay and in love with the novel’s eponymous character. Though a Google search indicates that Olear’s not exactly the first person to think of this, I admit I’d never considered the idea before, and his arguments are pretty persuasive. The article got me thinking about the other theories and alternate interpretations that are floating around about classic literary characters. Below, an investigation, and perhaps a few sides of characters you’ve never seen before.

Now we all know that I’m a student of the intersections between literature and psychology, but, well, it’s just too easy to get carried away with this kind of thing once you get started.

Writers writing about writing: ‘Why We Write’

Joan Didion had it right. In her 1976 essay “Why I Write,” originally published in the New York Times Book Review, she lays out the template in no uncertain terms: “In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions — with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating — but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.”

David L. Ulin, book critic for the Los Angeles Times, describes the newly released Why We Write: 20 Acclaimed Writers on How and Why They Do What They Do, edited by Meredith Maran.

See what writers including Mary Karr, Sara Gruen, James Frey, Susan Orlean, Rick Moody, Jane Smiley, Walter Mosley and Armistead Maupin have to say about their craft.

The Art of Marginalia

I, of course, could not pass up an article about the act of writing notes in the margins of books.

In addition to a neat photo of a well marked-up book, Jocelyn Kelley includes links to two other articles from the New Yorker and the New York Times.

16 Great Library Scenes in Film

When news broke last week that Dan Brown’s new novel will center on some sort of mystery surrounding Dante’s Inferno, I immediately began hoping that there is a nutty, fun scene of Robert Langdon racing around a library just like he raced around the Louvre in The Da Vinci Code.

And because I am who I am, it got me thinking about great movie library scenes that already exist. At first, I thought the list would be pretty short, but you know what? Hollywood loves a library. Some combination of ambiance, seclusion, hidden knowledge, and the sheer beauty of shelves upon shelves of books make libraries a fantastic film setting.

Jeff O’Neal, the editor of Book Riot, was surprised to find 16—SIXTEEN!—noteworthy library scenes in films.

Can you think of any that he left out?

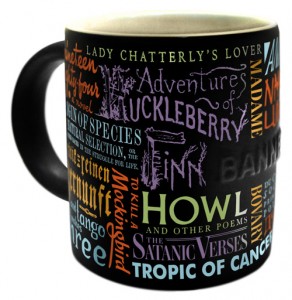

The Best Coffee Mugs for Book Lovers

With Valentine’s Day coming up fast, here’s a whole cupboard full of gift suggestions.

This one is my favorite. However if you would like to see more options go to the Spice Kitchen website.

Silent reading isn’t so silent, at least, not to your brain

The blogger at Neurotic Physiology, who says she has a Ph. D. in physiology, discusses some recent research into whether “silent reading” is truly silent to our brains. The study she’s describing involved only four participants (but there are good reasons for the small sample size, as NP explains) and is therefore quite limited. But the results are interesting:

What’s particularly new about this study is that it not only shows that silent reading causes high-frequency electrical activity in auditory areas, but it shows that these areas as specific to voices speaking a language. This activity was only present when the person was paying attention to the task. The authors believe that these results back up the hypothesis that we all produce an “inner voice” when reading silently. And it is enhanced by attention, suggesting that it’s probably not an automatic process, but something that occurs when we attentively process what we are reading. And the next time you read silently, remember that it’s not quite to silent to your brain.

Be sure to read the comments. They’ll have you contemplating the reading voice in your own head.

The Nuclear Monsters That Terrorized the 1950s

What would a visiting alien learn from Them!, Godzilla, and Attack of the 50-Foot Woman?

People who want to talk about the jumpy, kitschy, gloriously lurid movie genre we now know as 1950s sci-fi usually start with Susan Sontag. This is not because Sontag is a bug-eyed alien or 50 feet tall but because she wrote, in 1965, the definitive essay on Cold War dystopian fantasy: “The Imagination of Disaster.” “We live,” she claimed in that piece, “under continual threat of two equally fearful, but seemingly opposed, destinies: unremitting banality and inconceivable terror.” The job of science fiction was at once to “lift us out of the unbearably humdrum … by an escape into dangerous situations which have last-minute happy endings” and to “normalize what is psychologically unbearable, thereby inuring us to it.”

In other words, a good horror/fantasy/sci-fi flick provides a healthy dose of escapism, but it also keeps one eye fastened on what we wish to escape from.

Katy Waldman examines some of these classic movies and lists some conclusions we might draw from them:

- That science is amoral.

- That the universe exists in black-and-white.

- That women are scary. And sexy, too, just like the bomb itself.