A Fixation with Endings

There has been a lot of discussion lately about how novels end.

On Bad Endings

On The New Yorker‘s Page-Turner blog Joan Acocella declares:

Many of the world’s best novels have bad endings. I don’t mean that they end sadly, or on a back-to-work, all-is-forgiven note (e.g. “War and Peace,” “The Red and the Black,” “A Suitable Boy”), but that the ending is actually inartistic—a betrayal of what came before. This is true not just of good novels but also of books on which the reputation of Western fiction rests.

Coming to bad ends: stories that refuse closure

Imogen Russell Williams writes:

there is a tiny subset of unresolved and evil endings that leave their protagonists poised, helpless, on the brink of cataclysm, with the reader forever conscious, forever appalled and forever powerless to intervene. I call these Sword of Damocles endings, and avoid them like the black catarrh.

She lists the following books in this category:

- JB Priestley’s An Inspector Calls

- Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock

- Mo Hayder’s Hanging Hill

Endless fascination: in praise of novels without neat conclusions

In response to Imogen Russel Williams’s article, Lee Roach writes, “something troubled me deeply about Williams’s (and the vast reading public’s, I would argue) desire for our narratives to reach closure”:

But not those novels without end, steeped in ambiguity, those novels stay with us. We can’t shake them off, no matter how hard we try. They haunt us, mock us, they hang around waiting for us in the shadows, they disturb our working days, disrupt our sleep, torment us, force us to participate on their own terms. Much like real life does, novels without endings reveal to us the ambiguity that is crucial to our own desire to simply find out things for ourselves. You see, no matter how enjoyable, or how much good old, traditional “common sense” is to be found in our neatly packaged “endings”, I would argue there’s more reality to be found in a novel as supposedly impenetrable as Finnegans Wake, famous for having no beginning or end, than myriad formulaic novels that overtly yearn to capture what it is to be us in their well-worn beginnings, middles and ends. Viva ambiguity, I say!

Tyranny of the happy ending

Laura Miller weighs in over on Salon with the question, “Has our pep-talk-prone culture led readers to shun tragic literary classics?” Why have the tragedies of Shakespeare and the dark novels of George Eliot and Thomas Hardy declined drastically in popularity? Works like these are necessary for a full picture of the human condition:

Some aspects of the human experience can only be addressed in a tragic mode, and the truth of “Romeo and Juliet” — that the intransigence of elders often leads to the sacrifice of youth — is one of those aspects. The tragic Victorian novels of Eliot and Hardy deal with, among other subjects, the restrictions that class and gender roles impose on heroes and heroines who are capable of much more than their allotted place in society permits. Seeing the intellectual and spiritual yearnings of Maggie Tulliver (in “The Mill on the Floss”) and Jude Fawley (in “Jude the Obscure”) being crushed is agonizing, but providing either character with a miraculous escape from that fate would render the novels themselves pointless. Their point is precisely that sometimes the best people will fail, and fail utterly.

In the end, she adds:

By not embracing the tragic aspect of life, we not only lie to ourselves, we also begin to lose our ability to see the significance of a human life that transcends mere happiness. By treating art as if its only job is to cheer us up and on, we make it, and ourselves, a lot smaller.

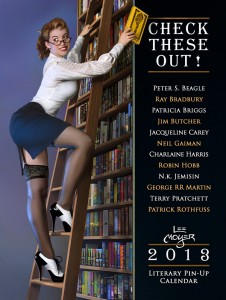

2013 Calendars for Book Nerds

On a happier note, Book Riot has some suggestions for book lovers in need of a new calendar for the upcoming year, including this one:

The Top 10 Novellas of All Time

Novellas are fictional works that contain between 20,000 and 40,000 words. Read why Johann Thorsson calls these works the top 10 novellas of all time:

- I Am Legend, Richard Matheson

- Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad

- Animal Farm, George Orwell

- A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens

- The Old Man and the Sea, Ernest Hemingway

- Metamorphosis, Franz Kafka

- Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck

- At The Mountains of Madness, H. P. Lovecraft

- The Turn of the Screw, Henry James

- A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess